Adventures in Karakalpakstan

- Ian Rosenberg

- Jul 13, 2025

- 11 min read

We said goodbye to Uzbekistan proper, crossing into a new world of deserts, unknown peoples, ancient history, plagued by one of the greatest ecological collapses in human history. Welcome to Karakalpakstan: a long-named, often forgotten-about region of the world that sparks the attention of very few. In fact, I was worried that our four days in the region would be too much, and perhaps it was, but I am glad we got to this odd destination regardless. The welcome sign into this semi-autonomous republic lays on the other side of the bridge over the Amu Darya river—the lifeline of the Silk Road.

Language Differences

Our first day, after crossing that bridge, we entered the nothingness that is the majority of rural Karakalpakstan. Sure, there were houses and some semblance of villages around, but overall, it just felt sandy, dusty, and empty. Something else that immediately hit was the language difference. Karakalpak is its own language, closely related to Kazakh, and filled with European loan words in the same way Uzbek is filled with Persian loan words. By the way, Uzbek’s closest sibling in the Turkic language family is Uyghur, despite their physical separation. Karakalpak also uses the Latin script, as Uzbek does, but with some notable differences. Instead of the apostrophes that Uzbek uses (such as in o’zbekiston, lag’man, etc.) to indicate altered pronunciations of the preceding letters, Karakalpak uses accents. For example, the city Nukus, which would be spelled No’kis if using Uzbek convention, is spelled Nókis in Karakalpak. It was a funny adjustment, and it seemed that Karakalpak was always distinct from Uzbek—they simply have a different aesthetic.

Also, Uzbek, over time, lost its vowel harmony (supplemental reading) from contact with Tajik and Persian, so many words in other Turkic languages that have an “a” will have an “o” in Uzbek. Notable examples are O’zbekison instead of Uzbekistan, Chaixona instead of Chaixana, and even the spellings of the cities of Toshkent and Buxoro instead of Tashkent and Bukhara. I’d say that after being used to these words in English, Kazakh, and Kyrgyz, I found it a little goofy that Uzbek had all these o’s in it. But that’s beside the point. In Karakalpakstan (or Qoraqalpog’iston in Uzbek and Qaraqalpaqstan in Karakalpak), everything is tri- or even quadlingual, with Uzbek, Karakalpak, Russian, and often English being on everything.

Khorezem Fortresses

Our first stop was some ancient fortresses of the Khorezem period. This period of history is not that well known about, but we do know that they were a significant force in trans-regional trade, as given by their fortresses being just as powerful trading posts as they were palaces.

We visited, throughout the day, five fortresses in various stages of preservation and reconstruction. The fortresses were from around the 1000s to 1200s, and were all sacked and pillaged by Genghis Khan and his forces. It was so interesting to me, this whole idea that I’m walking on the ruins of great cities destroyed by Genghis Khan, because that’s completely against what I had learned in Mongolia. In Mongolia, Genghis Khan is seen as the great hero, someone to be proud of, someone to name your banks and airports after and to put on your money. But over here, they see him completely differently. To the Kazakhs, to the Karakalpaks, to the Uzbeks, he was a force for evil. A warmongerer who tore apart civilizations, someone who destroyed generations of progress, of culture, of civilization.

Standing on top of these fortresses, I imagined looking out upon the now-ruins, imagining the buildings that used to be where now only the bases stand, seeing a horde of Mongols on horseback approach across the infinite desert. It was a visceral feeling—I think I even got some chills. I just kept on thinking that these places nowadays don’t stand not because they have fallen into disuse, but because they were deliberately, cruelly destroyed.

Each fortress was a little different, but they were all made of mud bricks in impressively complex architectural structures. Most of these had, at least remnants of, a still-standing wall, and most also had watch towers and slits in the walls for archers to shoot from. Though the details are not all exactly known about all the parts of all the fortresses, we do know that these were all cities designed with both defense and trade in mind. Often the trading post would be to the west side of the city, as to be in the shadow in the morning—the most frequent hours for trading—and each fortress’ watch tower was placed strategically with respect to the geography of the area.

As seems common in Central Asia, there was no supervision. Our guide only served to drive us from one fort to another. We could climb on whatever we wanted, go anywhere we wanted, and provided we didn’t destroy the history (too much) nothing was going to happen to us.

Getting to Nukus

We had the driver drop us off on the road to Nukus, as the others headed back, across the Karaklpak border, to Khiva. It took a surprisingly long time to find a ride—typically when we’ve hitchhiked around here we’ve had immediate success—but the ride we found was well worth the wait. The driver was this sweet older man who used to be a high-up in the Soviet army. He was stationed in Bulgaria, Afghanistan (the invasion which the Russians too failed), around the Middle East, and Eastern Europe. He’s retired now, living the ideal Karakalpak lifestyle in a Soviet-style concrete block apartment not far from where we were picked up.

Throughout our drive, we talked about the Karakalpak relation with Uzbekistan. It seems that they want to be generally left alone, but Uzbekistan is doing things to make the population grateful for them. This includes expanding UZ Railways service deep into Karakalpakstan, all the way to Qońirat (which we will pass through later) and redoing the roads. I would say the whole thing felt rather not contentious, but also, apparently riots just a few years ago led to several Karakalpaks getting killed over their desire for more autonomy and control over their lives.

Half way, we stopped for a melon break. He insisted on bringing us to this stand and he bought the three of us a giant melon to share. I can’t say I’m a huge fan of melon as it is, but this one was so juicy and sweet. And of course, I couldn’t say no to being force-fed by a Central Asian grandpa who wants us to enjoy the melon.

We arrived in Nukus after a few hours. The city is pretty decent sized, with more high rises than Almaty. It feels so Soviet, with wide boulevards, cement buildings everywhere, and a high degree of uniformity to every block of the city. The streets are in a predictable grid pattern, and gas and water pipes run willy nilly through the streets, bending around driveways around intersections. It feels like the culmination of all the urban infrastructure we’d seen in our time in Central Asia.

At the center of the city is its crown jewel: The State Museum of Arts of the Republic of Karakalpakstan named after I. V. Savitsky. Or in short, the Savitsky Museum. I’ll touch on why this is important later, but for now, I’ll say that it’s a grand building, with two massive flagpoles nearby. One flies the Uzbek flag, while the other boasts the markedly similar Karakalpak flag. The only difference is that the Karakalpak flag only has five stars on it, and the middle, white band of the Uzbek flag is colored yellow for the Karakalpak flag.

Muynaq

The second day, we went to Muynaq—a former wealthy town once known for its fishing. Today, the town is a shell of its former self, hardly sustaining local businesses and with a nearly non-existent tourism infrastructure. But we, like most who venture 4 hours from Nukus, were here for a single purpose. Boats. To put in context just how remote we were, the drive from Tashkent to Muynaq would be the same as the drive from New York City to Lansing. Except, the road infrastructure in Uzbekistan is a lot more…limited…than the US.

As I said, Muynaq used to be known for its fishing. It is now 55 miles from the sea that used to give it life. The Aral Sea was, for most of history, the third largest inland body of water in the world (by area), after the Caspian and Lake Superior. In the 1970s, the Soviets drained the Aral Sea in an effort to expand irrigation to cotton farming in the region. This project ended up draining the sea to 10% of what it used to be over the span of only a few years, leaving a new, artificial desert in its place made of harmful salt-sand caked in chemical remnants. The sea used to be home to an old Soviet chemical weapons testing facility, and when the sea dried up, the chemicals ended up on that “Aral Sand.” The people of the area both lost their way of life, the environment changed fundamentally around them, and they were being poisoned. It dragged this formerly prosperous region completely to shambles.

Driving through Muynaq now, you will see that most buildings are no longer in use. They have signs torn down, some signs left out of laziness, lights are off, windows are cracked, and no cars fill the parking spots. There’s not even taxis available to get from the Aral Sea Museum, which is 3 miles from the bus stop, back to town. We had to hitchhike.

The Aral Sea Museum was a small but important museum remembering, perhaps mourning, what the region used to have. It was filled with artwork depicting the thriving fishing and canning industries, the beautiful sunsets over the sea, the wildlife, and the boats always sailing. None of that exists anymore. The museum also highlights some efforts that are being taken to revive the sea, including creating artificial lakes and bringing the matter to the attention of the United Nations. With these new artificial lakes, two of which border Muynaq, the endemic species of birds that once left are now starting to return to the area. There is hope, but it seems that any hope of returning the sea back to its pre-1960s form has fully gone away.

Stepping outside, you see immediately a Soviet-style monument depicting the drop in water level over the decades, from the 1960s (pre-drainage) to now. And looking down, from the “shore” to the “sea,” but really to the seabed, you see the ships. Several ships sit on the ground, abandoned once the sea disappeared. Now, they sit, rusty and corroded, burning in the hot Karakalpak sun. We climbed around the ships for a while, and I certainly enjoyed getting to see core Naval Architecture principles, like framing and girder sizing, put into context!

I expected the time at the ships to be a lot more poignant than it was. Sure, all the ships were in utter disrepair, each with holes cut in the hull, the decks corroding, and any part that once moved now stuck with rust, but in general, it felt more like a playground than a spiritual experience. We had our thoughts in the museum, but once we left, it was more about enjoying the odd existence of these ships out of water.

To emphasize just how much of a ghost town Muynaq is nowadays, when we headed back into town (we had to hitchhike, as there was no way to call a ride to the museum), we needed to actively find a restaurant on Google Maps. Without that, we’d have been walking from empty building to empty building to no avail.

Savitsky Museum

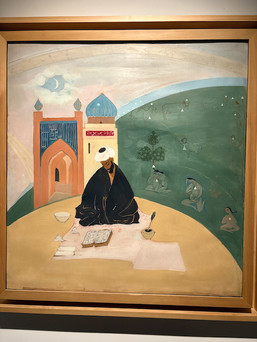

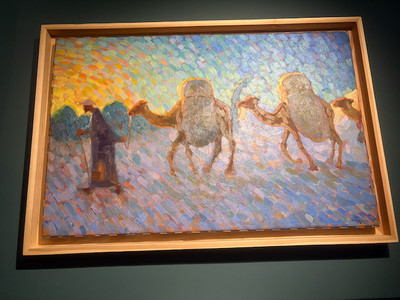

The Savitsky Museum is one of the biggest draws for Karakalpak tourism among the cultured and artistic. I actually didn’t know of the existence of the museum when we made the plans to go to Nukus, but it’s nearly impossible to miss when you’re actually there. The museum, with the over 80,000 personal collection pieces of Igor Savitsky, houses artwork Savitsky personally saved from the Soviet censor. Without his brave effort to save these avant-garde works that undermine the required socialist-realist style pushed by the government, we would have lost a whole generation of the depiction of Karakalpak experience, as well as countless artifacts related to the Karakalpak culture that go back centuries.

The museum features art from Savitsky as well as his contemporaries, many of which are the life in Uzbekistan and Karakalpakstan as seen through an Avant-Garde, distorting lens. These pieces touched on the beauty of Uzbekistan, its rich history that was being actively erased at the time, and brought the folk art traditions of the people into the 20th century.

One may notice that the museum does not look like any museum you’re used to. The walls are filled with paintings, often in close proximity to each other, in clusters of art instead of each piece by itself, special, alone. Savitsky said that he liked to pair non-related pieces of art together, creating a “party” on the wall (his words, not mine). Each piece talks to each other. Each piece complements, interacts, changes all the other pieces around it to create something that even the artist had no intent of creating. The meaning is derived from the whole, not the individual. Maybe that could be a poetic reflection on the Karakalpak nomadic lifestyle, but Savitsky was Ukrainian, so I’d venture to say I’m reading too far into it.

As I said, Savitsky is not Karakalpak. Instead, while being educated in Moscow, he became obsessed with this little-known culture, and uprooted his comfortable life as an educated elite to dedicate his efforts to preserving and advocating for the history and artistic traditions of the Karakalpaks. He traveled the region extensively, visiting villages and even being taken in as a grandmother who treated him as her own. Among his explorations, he understood what was important in saving out of this at-risk culture, and succeeded. Thanks to Savitsky, the Karakalpaks, their traditions, and culture survive until today.

Plov!

On a final note, Zack and I, out of boredom (Nukus is not the most exciting place in the world to be) decided that we should cook one night. We ran around the Nukus market, which is amazingly tame compared to the other markets we’d visited, buying vegetables, spices, dried barberries, oil, meat, bread, melon, and tea from the various vendors. Amazingly, we could not find the spice market. I’m convinced we came too late in the day for it. So we had to settle for buying a pre-made plov spice packet.

Plov is just rice pilaf, loaded with oil and spiced in a particular way. Usually, the meat is lamb, but Zack and I bought some meat from the vendor that we think was beef? But we’re not quite sure. We just pointed and told the lady “that one.”

To make the plov, you first cook the meat with a lot of oil. Once done, you remove the meat and cook the vegetables in the same oil, adding more if needed. Then, you put the meat back in and pour in all the uncooked rice, covering the entire rice-meat-vegetable mixture with water. You simmer it, letting them all cook together, as the rice cooks in the pan. The result is rice cooked with the flavors of everything else in the dish.

The plov came out pretty good, considering the very limited things we were working with. The kitchen was not well-equipped, and we, again, could not find the spices. Unfortunately, I think it needed a little more spice, as it tasted mostly of the yellow pepper we put in it. But still, this recipe was highly successful, and when I get my hands on some more spices back home, I’ll certainly make a more flavorful version.

And that concludes our activities in Uzbekistan. I really, really enjoyed our time there. I think it’s better for someone who enjoys traveling slower, and someone who enjoys the vibe of a place more than someone who is concerned with always having something to do or go. If you like long walks around beautiful cities, exploring every nook and cranny for little relics of history ancient or modern, this should certainly be a bucket list country for you. It’s really safe (I didn’t touch on a story when I didn’t feel safe, but the two times in these 13 days I felt unsafe were both with Russians, not Uzbeks), and though not as affordable as Kyrgyzstan, it’s still wicked cheap. But overall, what a beautiful place filled with a rich tradition of craftsmanship and a hyper fixation on beauty and preservation.

Comments